The significance and meaning of a Hindu Temple[edit]

Hindu temple reflects a synthesis of arts, the ideals of

dharma, beliefs, values and the way of life cherished under Hinduism. It is a link between man, deities, and the Universal

Purusa in a sacred space.

[14]

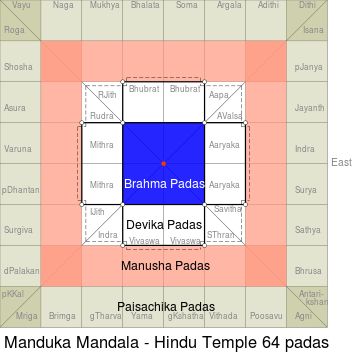

The 9x9 (81) grid ‘’Parama Sayika’’ layout plan (above) found in large ceremonial Hindu Temples. It is one of many grids used to build Hindu temples. In this structure of symmetry, each concentric layer has significance. The outermost layer, Paisachika padas, signify aspects of Asuras and evil; while inner Devika padas signify aspects of Devas and good. In between the good and evil is the concentric layer of Manusha padas signifying human life; All these layers surround Brahma padas, which signifies creative energy and the site for temple’s primary idol for darsana. Finally at the very center of Brahma padas is Grabhgriya (Purusa Space), signifying Universal Principle present in everything and everyone.

[2]

In ancient Indian texts, a temple is a place for

Tirtha - pilgrimage.

[2] It is a sacred site whose ambience and design attempts to symbolically condense the ideal tenets of Hindu way of life.

[14] All the cosmic elements that create and sustain life are present in a Hindu temple - from fire to water, from images of nature to deities, from the feminine to the masculine, from the fleeting sounds and incense smells to the eternal nothingness yet universality at the core of the temple.

[2]

Susan Lewandowski states

[5] that the underlying principle in a Hindu temple is built around the belief that all things are one, everything is connected. The pilgrim is welcomed through 64-grid or 81-grid mathematically structured spaces, a network of art, pillars with carvings and statues that display and celebrate the four important and necessary principles of human life - the pursuit of

artha (prosperity, wealth), the pursuit of

kama (pleasure, sex), the pursuit of

dharma (virtues, ethical life) and the pursuit of

moksha (release, self-knowledge).

[15][16] At the center of the temple, typically below and sometimes above or next to the deity, is mere hollow space with no decoration, symbolically representing

Purusa, the Supreme Principle, the sacred Universal, one without form, which is present everywhere, connects everything, and is the essence of everyone. A Hindu temple is meant to encourage reflection, facilitate purification of one’s mind, and trigger the process of inner realization within the devotee.

[2] The specific process is left to the devotee’s school of belief. The primary deity of different Hindu temples varies to reflect this spiritual spectrum.

In Hindu tradition, there is no dividing line between the secular and the sacred.

[5] In the same spirit, Hindu temples are not just sacred spaces, they are also secular spaces. Their meaning and purpose have extended beyond spiritual life to social rituals and daily life, offering thus a social meaning. Some temples have served as a venue to mark festivals, to celebrate arts through dance and music, to get married or commemorate marriages,

[17] commemorate the birth of a child, other significant life events, or mark the death of a loved one. In political and economic life, Hindu temples have served as a venue for the succession within dynasties and landmarks around which economic activity thrived.

[18]

The forms and designs of Hindu Temples[edit]

Almost all Hindu temples take two forms: a house or a palace. A house-themed temple is a simple shelter which serves as a deity’s home. The temple is a place where the devotee visits, just like he or she would visit a friend or relative. In Bhakti school of Hinduism, temples are venues for

puja, which is a hospitality ritual, where the deity is the honored, and where devotee calls upon, attends to and connects with the deity. In other schools of Hinduism, the person may simply perform jap, or meditation, or yoga, or introspection in his or her temple.

A palace-themed temples are more elaborate, often monumental architecture.

The site[edit]

The appropriate site for a temple, suggest ancient Sanskrit texts, is near water and gardens, where lotus and flowers bloom, where swans, ducks and other birds are heard, where animals rest without fear of injury or harm.

[2] These harmonious places were recommended in these texts with the explanation that such are the places where gods play, and thus the best site for Hindu temples.

[2][5]

Hindu temple sites cover a wide range. The most common sites are those near water bodies, embedded in nature, such as the above at Badami, Karnataka.

The gods always play where lakes are,

where the sun’s rays are warded off by umbrellas of lotus leaf clusters,

and where clear waterpaths are made by swans

whose breasts toss the white lotus hither and thither,

where swans, ducks, curleys and paddy birds are heard,

and animals rest nearby in the shade of Nicula trees on the river banks.

The gods always play where rivers have for their braclets

the sound of curleys and the voice of swans for their speech,

water as their garment, carps for their zone,

the flowering trees on their banks as earrings,

the confluence of rivers as their hips,

raised sand banks as breasts and plumage of swans their mantle.

The gods always play where groves are near, rivers, mountains and springs, and in towns with pleasure gardens.

—Brhat Samhita 1.60.4-8,

6th Century CE[19]

While major Hindu temples are recommended at sangams (confluence of rivers), river banks, lakes and seashore,

Brhat Samhita and

Puranas suggest temples may also be built where a natural source of water is not present. Here too, they recommend that a pond be built preferably in front or to the left of the temple with water gardens. If water is neither present naturally nor by design, water is symbolically present at the consecration of temple or the deity. Temples may also be built, suggests

Visnudharmottara in Part III of Chapter 93,

[20] inside caves and carved stones, on hill tops affording peaceful views, mountain slopes overlooking beautiful valleys, inside forests and hermitages, next to gardens, or at the head of a town street.

The manuals[edit]

Ancient builders of Hindu temples created manuals of architecture, called

Vastu-Sastra (literally, science of dwelling, Vas-tu is a composite Sanskrit word Vas means reside, tu means you); these contain Vastu-Vidya (literally, knowledge of dwelling).

[21] There exist many Vastu-Sastras on the art of building temples, such as one by Thakkura Pheru, describing where and how temples should be built.

[22][23] By the 6th century AD, Sanskrit manuals for constructing palatial temples were in circulation in India.

[24] Vastu-Sastra manuals included chapters on home construction, town planning,

[21] and how efficient villages, towns and kingdoms integrated temples, water bodies and gardens within them to achieve harmony with nature.

[25][26] While it is unclear, states Barnett,

[27] as to whether these temple and town planning texts were theoretical studies and if or when they were properly implemented in practice, the manuals suggest that town planning and Hindu temples were conceived as ideals of art and integral part of Hindu social and spiritual life.

[21]

Ancient India produced many Sanskrit manuals for Hindu temple design and construction, covering arrangement of spaces (above) to every aspect of its completion. Yet, the Silpins were given wide latitude to experiment and express their creativity.

[28]

The

Silpa Prakasa of Odisha, authored by Ramacandra Bhattaraka Kaulacara sometime in ninth or tenth century CE, is another Sanskrit treatise on Temple Architecture.

[29] Silpa Prakasa describes the geometric principles in every aspect of the temple and symbolism such as 16 emotions of human beings carved as 16 types of female figures. These styles were perfected in Hindu temples prevalent in eastern states of India. Other ancient texts found expand these architectural principles, suggesting that different parts of India developed, invented and added their own interpretations. For example, in

Saurastra tradition of temple building found in western states of India, the feminine form, expressions and emotions are depicted in 32 types of

Nataka-stri compared to 16 types described in

Silpa Prakasa.

[29] Silpa Prakasa provides brief introduction to 12 types of Hindu temples. Other texts, such as

Pancaratra Prasada Prasadhana compiled by Daniel Smith

[30] and Silpa Ratnakara compiled by Narmada Sankara

[31] provide a more extensive list of Hindu temple types.

Ancient Sanskrit manuals for temple construction discovered in Rajasthan, in northwestern region of India, include Sutradhara Mandana’s

Prasadamandana (literally, manual for planning and building a temple).

[32] Manasara, a text of South Indian origin, estimated to be in circulation by the 7th century AD, is a guidebook on South Indian temple design and construction.

[5][33] Isanasivagurudeva paddhati is another Sanskrit text from the 9th century describing the art of temple building in India in south and central India.

[34][35] In north India,

Brihat-samhita by

Varāhamihira is the widely cited ancient Sanskrit manual from 6th century describing the design and construction of

Nagara style of Hindu temples.

[28][36][37]

Elements of a Hindu temple in Kalinga style. There are many Hindu temple styles, but they almost universally share common geometric principles, symbolism of ideas, and expression of core beliefs.

[2]

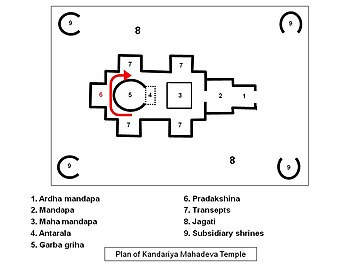

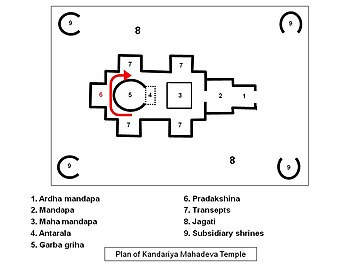

The plan[edit]

A Hindu temple design follows a geometrical design called

vastu-purusha-mandala. The name is a composite Sanskrit word with three of the most important components of the plan.

Mandala means circle,

Purusha is universal essence at the core of Hindu tradition, while

Vastu means the dwelling structure.

[38] Vastupurushamandala is a

yantra.

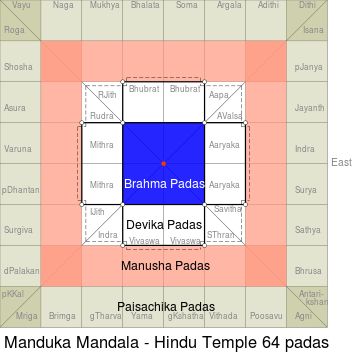

[22] The design lays out a Hindu temple in a symmetrical, self-repeating structure derived from central beliefs, myths, cardinality and mathematical principles.

The four cardinal directions help create the axis of a Hindu temple, around which is formed a perfect square in the space available. The circle of mandala circumscribes the square. The square is considered divine for its perfection and as a symbolic product of knowledge and human thought, while circle is considered earthly, human and observed in everyday life (moon, sun, horizon, water drop, rainbow). Each supports the other.

[2] The square is divided into perfect 64 (or in some cases 81) sub-squares called padas.

[28][39] Each pada is conceptually assigned to a symbolic element, sometimes in the form of a deity. The central square(s) of the 64 or 81 grid is dedicated to the Brahman (not to be confused with Brahmin), and are called Brahma padas.

The 8x8 (64) grid Manduka Hindu Temple Floor Plan, according to Vastupurusamandala. The 64 grid is the most sacred and common Hindu temple template. The bright saffron center, where diagonals intersect above, represents the Purusha of Hindu philosophy.

[2][28]

The 49 grid design is called Sthandila and of great importance in creative expressions of Hindu temples in South India, particularly in ‘‘Prakaras’’.

[40] The symmetric Vastu-purusa-mandala grids are sometimes combined to form a temple superstructure with two or more attached squares.

[41] The temples face sunrise, and the entrance for the devotee is typically this east side. The mandala pada facing sunrise is dedicated to Surya deity (Sun). The Surya pada is flanked by the padas of Satya (Truth) deity on one side and

Indra (king of gods) deity on other. The east and north faces of most temples feature a mix of gods and demi-gods; while west and south feature demons and demi-gods related to the underworld.

[42] This vastu purusha mandala plan and symbolism is systematically seen in ancient Hindu temples on Indian subcontinent as well as those in southeast Asia, with regional creativity and variations.

[43][44]

Beneath the mandala’s central square(s) is the space for the formless shapeless all pervasive all connecting Universal Spirit, the

highest reality, the purusha.

[45] This space is sometimes referred to as garbha-griya (literally womb house) - a small, perfect square, windowless, enclosed space without ornamentation that represents universal essence.

[38] In or near this space is typically a murti (idol). This is the main deity idol, and this varies with each temple. Often it is this idol that gives the temple a local name, such as Visnu temple, Krishna temple, Rama temple, Narayana temple, Siva temple, Lakshmi temple, Ganesha temple, Durga temple, Hanuman temple, Surya temple, and others.

[14] It is this garbha-griya which devotees seek for ‘‘darsana’’ (literally, a sight of knowledge,

[46] or vision

[38]).

Above the vastu-purusha-mandala is a superstructure with a dome called

Shikhara in north India, and

Vimana in south India, that stretches towards the sky.

[38] Sometimes, in makeshift temples, the dome may be replaced with symbolic bamboo with few leaves at the top. The vertical dimension's cupola or dome is designed as a pyramid, conical or other mountain-like shape, once again using principle of concentric circles and squares (see below).

[2] Scholars suggest that this shape is inspired by cosmic mountain of Meru or Himalayan Kailasa, the abode of gods according to Vedic mythology.

[38]

A Hindu temple has a Sikhara (Vimana or Spire) that rises symmetrically above the central core of the temple. These spires come in many designs and shapes, but they all have mathematical precision and geometric symbolism. One of the common principles found in Hindu temple spires is circles and turning-squares theme (left), and a concentric layering design (right) that flows from one to the other as it rises towards the sky.

[2][47]

In larger temples, the central space typically is surrounded by an ambulatory for the devotee to walk around and ritually circumambulate the Purusa, the universal essence.

[2] Often this space is visually decorated with carvings, paintings or images meant to inspire the devotee. In some temples, these images may be stories from Hindu Epics, in others they may be Vedic tales about right and wrong or virtues and vice, in some they may be idols of minor or regional deities. The pillars, walls and ceilings typically also have highly ornate carvings or images of the four just and necessary pursuits of life - kama, artha, dharma and moksa. This walk around is called

pradakshina.

[38]

Large temples also have pillared halls called mandapa. One on the east side, serves as the waiting room for pilgrims and devotees. The mandapa may be a separate structure in older temples, but in newer temples this space is integrated into the temple superstructure. Mega temple sites have a main temple surrounded by smaller temples and shrines, but these are still arranged by principles of symmetry, grids and mathematical precision. An important principle found in the layout of Hindu temples is mirroring and repeating fractal-like design structure,

[48] each unique yet also repeating the central common principle, one which Susan Lewandowski refers to as “an organism of repeating cells”.

[18]

An illustration of Hindu temple Spires (Sikhara, Vimana) built using concentric circle and rotating-squares principle. The left is from Vijayanagar in

Karnataka, the right is from Pushkar in

Rajasthan.

The ancient texts on Hindu temple design, the

Vastupurusamandala and

Vastu Sastras, do not limit themselves to the design of a Hindu temple.

[49] They describe the temple as a holistic part of its community, and lay out various principles and a diversity of alternate designs for home, village and city layout along with the temple, gardens, water bodies and nature.

[2][25]

- Exceptions to the square grid principle

Predominant number of Hindu temples exhibit the perfect square grid principle.

[50] However, there are some exceptions. For example, the Teli-ka-mandir in

Gwalior, built in the 8th century CE is not a square but is a rectangle in 2:3 proportion. Further, the temple explores a number of structures and shrines in 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 2:5, 3:5 and 4:5 ratios. These ratios are exact, suggesting the architect intended to use these harmonic ratios, and the rectangle pattern was not a mistake, nor an arbitrary approximation. Other examples of non-square harmonic ratios are found at Naresar temple site of Madhya Pradesh and Nakti-Mata temple near Jaipur, Rajasthan.

Michael Meister suggests that these exceptions mean the ancient Sanskrit manuals for temple building were guidelines, and Hinduism permitted its artisans flexibility in expression and aesthetic independence.

[28]

The symbolism[edit]

A Hindu temple is a symbolic reconstruction of the universe and universal principles that make everything in it function.

[2][51] The temples reflect Hindu philosophy and its diverse views on cosmos and Truths.

[48][52]

Hinduism has no traditional ecclesiastical order, no centralized religious authorities, no governing body, no prophet(s) nor any binding holy book; Hindus can choose to be polytheistic, pantheistic, monistic, or atheistic.

[53] Within this diffuse and open structure, spirituality in Hindu philosophy is an individual experience, and referred to as kṣaitrajña (Sanskrit: क्षैत्रज्ञ

[54]). It defines spiritual practice as one’s journey towards

moksha, awareness of self, the discovery of higher truths, true nature of reality, and a consciousness that is liberated and content.

[55][56] A Hindu temple reflects these core beliefs. The central core of almost all Hindu temples is not a large communal space; the temple is designed for the individual, a couple or a family - a small, private space where he or she experiences darsana.

Darsana is itself a symbolic word. In ancient Hindu scripts, darsana is the name of six methods or alternate viewpoints of understanding Truth.

[57] These are Nyaya, Vaisesika, Sankhya, Yoga, Mimamsa and Vedanta - each of which flowered into their own schools of Hinduism, each of which are considered valid, alternate paths to understanding Truth and realizing Self in the Hindu way of life.

From names to forms, from images to stories carved into the walls of a temple, symbolism is everywhere in a Hindu temple. Life principles such as the pursuit of joy, sex, connection and emotional pleasure (kama) are fused into mystical, erotic and architectural forms in Hindu temples. These motifs and principles of human life are part of the sacred texts of Hindu, such as its Upanishads; the temples express these same principles in a different form, through art and spaces. For example, Brihadaranyaka Upanisad at 4.3.21, recites:

In the embrace of his beloved a man forgets the whole world,

everything both within and without;

in the same way, he who embraces the Self,

knows neither within nor without.